|

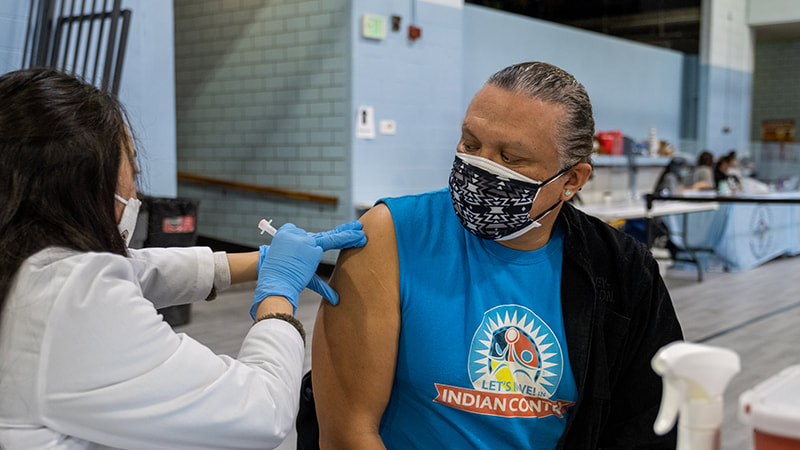

Written By Kristin Jones, The Colorado Trust, 3/24/2021 The Denver Indian Center on Morrison Road is a place for community events—elder luncheons, classes, pow wows. A year ago, it was closed for gatherings. That began to change in December, after staff at Denver Indian Health and Family Services drove to Albuquerque, N.M. to pick up the first vial of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine from the Indian Health Center there. Now, every Friday from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m., members of Denver’s urban Native community arrive to get vaccinated. Among Indigenous communities both on reservations and in urban areas, the COVID-19 vaccine is being distributed by the federal Indian Health Service, in a parallel effort to that of the states. As of March 16, the Indian Health Service had distributed 9,300 vaccine doses in Colorado to the Ute Mountain Ute Health Center, the Southern Ute Health Center, and Denver Indian Health and Family Services, according to an emailed statement. The process is going quickly, allowing providers to expand eligibility to a much larger cohort than otherwise would have access to the vaccine. In southwest Colorado, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe started offering COVID-19 vaccines to any adult, Native or not, who can make it to their vaccination events in Towaoc. On a recent Friday in March, Denver Indian Health and Family Services was offering vaccines to tribal members as young as 18, provided they had a high-risk medical condition. Some non-Native people who live in the same households as tribal members or who work in Native-run organizations have been able to get vaccinated, too. A campaign by Denver Indian Health and Family Services to promote the vaccine has focused on its importance in protecting elders. Adrianne Maddux, a member of Hopi Nation and executive director of Denver Indian Health and Family Services, was at the event. The social aspect is important, Maddux started saying. And then, as if on cue, Darius Lee Smith, who directs Denver’s Anti-Discrimination Office and is Navajo, stepped out of his place in line to greet her. Smith was there with his 25-year-old daughter, Savannah. They were both scheduled for their second dose of the Moderna vaccine. “See? That’s what I mean about it being a community reunion,” said Maddux. Friends who haven’t seen each other in months run into each other here. She sees people posting about it on social media. Indigenous communities have been especially hard hit by COVID-19. American Indians and Alaska Natives are more than twice as likely as white Americans to have died of COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Darius Lee Smith, who is 53, was hospitalized with COVID-19 in November. He’s a runner and he’s always been healthy, so he wasn’t particularly worried about it, he said. Except for a few bad moments: when he was checking into the hospital, for instance, and was asked who would make decisions for him if he had to be put on a ventilator. Then, a few days after Darius Lee Smith was discharged from the hospital, his mother was admitted. “I was terrified,” he said. “Both because she’s 78 and because I felt guilty about giving it to her.” Both mother and son have made a full recovery, he said. Savannah Lee Smith was months away from graduating with a master’s degree in public health, specializing in Native American health, when COVID-19 shut things down a year ago. She worked as a contact tracer for a while before getting a job as a research assistant at the Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health at the Colorado School of Public Health. (Colorado Trust funding established an endowed chair position at the Centers in 2015.) “Some people my age feel guilty” about getting the vaccine, Savannah Lee Smith said. “But I think if you have the opportunity to get the vaccine, definitely take it.” Nearby, Shad Wright, a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, was getting his second shot, too. The Indian Health Service called the 43-year-old a few weeks ago to ask him whether he wanted the vaccine. He said he did, and that was that. The side effects from the first vaccine weren’t so bad, he said: “All I had was a dead arm.” The success of the vaccine rollout efforts are a point of pride in Native communities, said Darius Lee Smith. “How they’re distributing vaccines is an exercise in tribal sovereignty,” he said. Rachel Bryan-Auker, who is Kaigani Haida and Tlingit, is tribal liaison for the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. She said the state health agency works closely with the tribes on vaccine distribution and is proud of their collaboration. “Tribes, and the Urban Indian Health Programs, have shown incredible leadership throughout the response,” said Bryan-Auker. (The Urban Indian Health Programs are nonprofits, including Denver Indian Health and Family Services, that are contracted by the Indian Health Service to provide health care to tribal members.) “We really commend them at how effective they’ve been in vaccinating communities. We’re always learning from them.” Addressing hesitancy, one person at a time Patrick Kills Crow, who is 70 years old and a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, was nervous initially about getting the vaccine when it first became available to him in early January. Kills Crow has good reasons to be distrustful of anything that smacks of colonization. His parents sent him and his brother to a Catholic boarding school from third grade through high school because they couldn’t afford to take care of the boys. The teachers hit the kids for speaking Sioux, and cut their hair frequently as a form of punishment and to strip them of their culture. Before Kills Crow had even turned 18, he was fighting in Vietnam—an experience that still haunts him. “I don’t know if I should trust the government,” said Kills Crow. But he trusted other people in the Indigenous community, including the people he works with as a consultant at the nonprofit Denver Indian Family Resource Center. (The center is a recent grantee of The Colorado Trust.) And he had seen the devastation that the disease has caused. A niece living in Nebraska died of COVID-19, leaving children behind; she was in her mid-30s. So Kills Crow got the vaccine. Now, a big part of his job is to talk to other elders about the COVID-19 vaccine. He recently convinced another two people to let him give them a ride to the vaccine clinic. “They agreed to take the vaccine because they want to be there for their grandkids,” he said. Despite the relative ease of access to vaccines for Native people living in Denver, there are still steep barriers to access for some—like Kills Crow’s sister-in-law, who is housebound because of health problems. There’s also a lot of misinformation, especially among people who are disconnected from their communities. Kills Crow has experienced being homeless, and empathizes with people he talks to who are unhoused. He sees the way bad information spreads about how the vaccines cause terrible side effects among people with diabetes or mess with DNA (they don’t). “Everybody’s a doctor,” said Kills Crow. His method of gaining trust is unlikely to be promoted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but it works: “I bribe them with cigarettes or McDonald’s.” Tara McLain Manthey, a member of the Osage Nation, is executive director at the Denver Indian Family Resource Center where Kills Crow works. She said the ability to vaccinate staff working at the center has been crucial to resuming in-person services that were impossible in the fall. Many of these services are vital. Among the center’s responsibilities are providing services to Indigenous families in the child welfare system, including supervised visits between parents and children as well as parenting classes and other resources. Because of the U.S. history of separating Indigenous families, it’s important that this support comes from within Native communities. But during the COVID-19 surge in the fall, the center was unable to go to people’s houses or invite them in. Now, after being vaccinated, staff plan to go back to supervising parental visits at their offices near City Park. From Manthey’s perspective, the work of Kills Crow and others provides a model for how vaccines could roll out for everyone, especially as they become more widely available. Indigenous organizations shared a single-minded focus on the vaccine, she said, and used their best available resource: their people. Kills Crow "is doing it one by one,” said Manthey. “That’s the future of the vaccination effort.” For full article, click here.

Comments are closed.

|

Did you miss our last newsletter? Now you can read it here:

Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

about us |

services |

resources |

connect |

Ph. (303) 953-6600

Clinic Fax. (303) 781-4333 Admin Fax. (303) 643-5885 2880 W. Holden Place Denver, Colorado 80204 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed