|

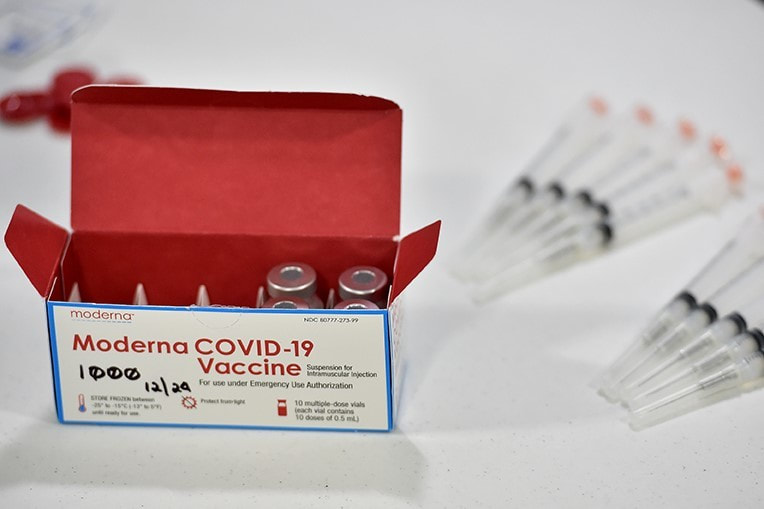

#BeAGoodRelative and get vaccinated! Protecting the ones you love means protecting yourself. If you are interested in receiving the COVID-19 Vaccine, contact us to schedule your appointment.

For medical information regarding the COVID-19 Vaccine please call DIHFS at 303-953-6600 Native health professionals say vaccine is safe for American Indians and Alaska Natives

Seattle, WA—In a recent op-ed published in Indian Country Today, Dr. Bruce Davidson advised American Indians and Alaska Natives to avoid receiving the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine. The following statement from Abigail Echo-Hawk and Dr. Mary Owen may be quoted in part or in full. “As public health professionals who have a combined 40 years of experience working with and caring for American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) people, we are disappointed and concerned by claims by Dr. Bruce Davidson, advising AI/AN people to avoid the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine. We believe his statements will lead to the deaths of American Indian and Alaska Native people by increasing hesitancy toward a COVID-19 vaccine. Dr. Davidson’s narrow-minded claims—and irresponsible and reckless interpretation of data—further fuels vaccine distrust in Native communities. And this comes at a time when AI/AN people are dying of COVID-19 at the highest rates in the country, and when rapid vaccination of our community members is paramount to saving lives. During this time, we shouldn’t have to question the words of doctors, but in this case, we must. Misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines has been—and continues to be—dangerous and puts our elders and communities at risk. AI/AN communities need to have access to accurate information from trusted sources in order to make informed decisions about COVID-19 vaccines. Indian Country has been leaders in the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines. We are starting to see some reservations and villages over 50% vaccinated, while cities look to urban Indian health programs for solutions. We are getting closer and closer to the finish line, but it will be claims like Dr. Davidson’s that will slow us down from crossing it. Like the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, the Johnson & Johnson vaccine is safe, effective, and necessary if Indian Country is going to win the fight against COVID-19.” Written by The Denver Channel, Adi Guajardo, Jan. 8, 2021

DENVER — The Denver Indian Health and Family Services held their first clinic in Denver on Friday and gave the Moderna shot to 120 Native Americans. The pandemic has taken a cruel toll on American Indians and Alaska Natives across the U.S. They make up 0.56% of the Colorado population and 0.65% of COVID-19 deaths in the state, according to the state health department website. A study by the Centers for Disease and Prevention (CDC) found that Native Americans are nearly twice as likely to die of COVID-19 than white people. The pandemic has taken a cruel toll on American Indians and Alaska Natives across the U.S. They make up 0.56% of the Colorado population and 0.65% of COVID-19 deaths in the state, according to the state health department website. A study by the Centers for Disease and Prevention (CDC) found that Native Americans are nearly twice as likely to die of COVID-19 than white people. Charlene Irani is a board member with the Denver Indian Health and Family Services. She received her vaccine on Wednesday. On Friday, she helped people fill out forms and prepared them for their inoculation. Irani calls COVID-19 "the invisible virus." She says it’s taken the lives of her people. “I’ve had friends die because they didn’t believe it was real,” Irani said. “This is real.” Denver Indian Health and Family Services set up a clinic at the Denver Indian Center. Staff scheduled more than 100 of their patients who met the state vaccination phase system for an appointment to get the Moderna vaccine. Karen Hoffman-Welch, the director of primary care for Denver Indian Health and Family Services, says their patients were nervous and concerned about the shot. "(They had) a lot of questions. Are they going to get sick? Are we actually giving them the virus?" Hoffman-Welch recalled. To help put them at ease, staff helped answer their questions and provided facts about the COVID-19 vaccine. “We called about 200 patients and were able to get about 150 or so to say yes,” Hoffman-Welch said. The history between the government and Native Americans fuels hesitation about getting the vaccine. “There is a historical kind of trauma when it comes to the medical society because they have been tested without their permission,” Hoffman-Welch said. She adds that American Indians are more likely to take advice from community leaders than medical experts. It's why advocates like Irani are also getting vaccinated. Irani says it's vital to share her story and assure her people the shot is safe. “I’m feeling great, I have to tell you I didn’t get any of the side effects,” Irani said. She’s pleading with her community to get the vaccine. “This vaccine is here to help us, not to hinder or hurt us,” she said. Delmar Hamilton got his shot on Friday. He says too many people are dying and he wants to help protect and preserve his history. “The tribal thing is an oral tradition and if there isn’t anybody to pass that oral tradition — it’s lost forever,” Hamilton said. The vaccines came from the Indian Health Service, a federal health program for American Indians and Alaskan Natives. University of Colorado pharmacy students volunteered to give the shots. Hoffman-Welch says they were hoping to vaccinate 150 people but only reached 120. The process is targeted and each does must be tracked. “Each vial has ten doses and once that vial has been opened I have to use it within 12 hours, so I have to make sure I have at least ten people every time we open a vial to give them the vaccine,” she said. Any doses left over from Friday’s clinic will be frozen in storage. In four weeks, those who received their shots will return for their second dose. Hoffman-Welch expects to set up more clinics in the coming weeks. Shots will only be administered by appointment. If you are an American Indian or an Alaskan Native and want to get on the list to get vaccinated, you can sign up for free online by clicking here and registering as a new patient. The Denver Indian Health and Family Services will contact people by phone to schedule appointments if they meet the phase requirement. You can also call (303) 953-6600 to set up an appointment. For full article click here. |

Did you miss our last newsletter? Now you can read it here:

Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

about us |

services |

resources |

connect |

Ph. (303) 953-6600

Clinic Fax. (303) 781-4333 Admin Fax. (303) 643-5885 2880 W. Holden Place Denver, Colorado 80204 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed